Michael Graves Architecture and the Lost Art of Drawing

Information technology has become fashionable in many architectural circles to declare the death of drawing. What has happened to our profession, and our fine art, to crusade the supposed end of our most powerful means of conceptualizing and representing compages? The computer, of form. With its tremendous ability to organize and present data, the estimator is transforming every aspect of how architects work, from sketching their first impressions of an idea to creating complex construction documents for contractors. For centuries, the substantive "digit" (from the Latin "digitus") has been defined as "finger," but now its adjectival form, "digital," relates to data.

Are our easily condign obsolete as creative tools? Are they being replaced by machines? And where does that leave the architectural creative process? Today architects typically utilise estimator-aided design software with names like AutoCAD and Revit, a tool for "building information modeling." Buildings are no longer just designed visually and spatially; they are "computed" via interconnected databases.

Most architects routinely utilise these and other software programs, specially for construction documents, but likewise for developing designs and making presentations. There'southward nothing inherently problematic near that, as long as it'southward not just that.

Architecture cannot divorce itself from drawing, no matter how impressive the technology gets. Drawings are non just end products: they are function of the thought process of architectural design. Drawings express the interaction of our minds, eyes and easily. This last statement is absolutely crucial to the difference betwixt those who draw to anticipate architecture and those who utilise the computer.

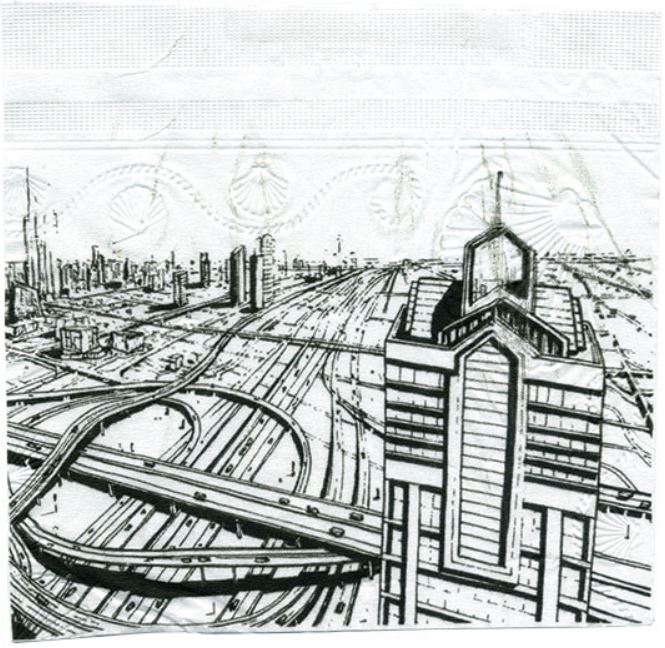

Information technology has been said that architectural drawing can exist divided into three types; the "referential sketch," the "preparatory study" and the "definitive drawing." The definitive drawing, the final and most developed of the iii, is almost universally produced on the figurer nowadays, and that is appropriate. But what about the other two? What is their value in the creative process? What can they teach usa?

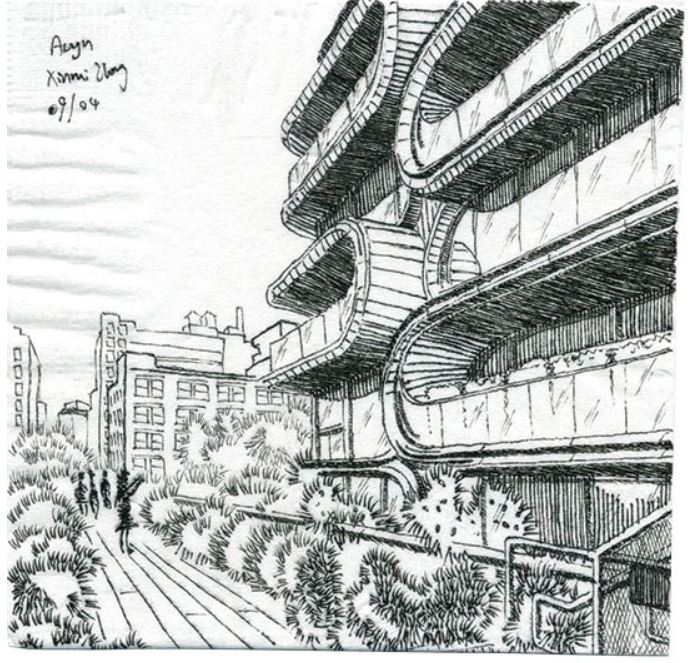

The referential sketch serves as a visual diary, a record of an architect's discovery. It can be as unproblematic every bit a shorthand annotation of a design concept or can describe details of a larger composition. It might not even be a drawing that relates to a building or whatever time in history. It'south not likely to stand for "reality," but rather to capture an thought.

These sketches are thus inherently fragmentary and selective. The drawing is a reminder of the idea that caused one to record it in the first identify. That visceral connection, that thought process, cannot be replicated by a computer.

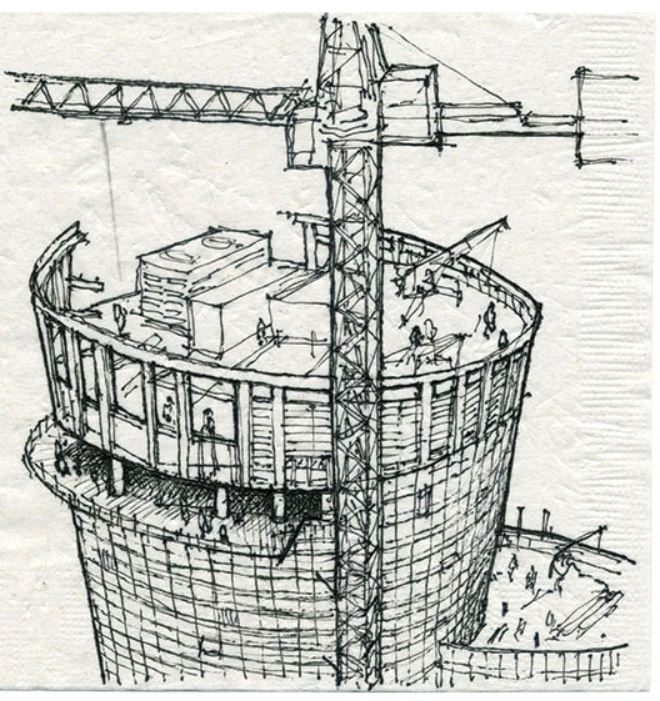

The 2d blazon of cartoon, the preparatory study, is typically role of a progression of drawings that elaborate a design. Similar the referential sketch, information technology may not reverberate a linear process. (computer-aided blueprint is often much more linear.) Designers may opt to depict on translucent yellowish tracing newspaper, which allows them to layer 1 drawing on peak of some other, edifice on what they've drawn before and, again, creating a personal, emotional connection with the piece of work.

With both of these types of drawings, at that place is a certain joy in their cosmos, which comes from the interaction between the heed and the hand. Our physical and mental interactions with drawings are formative acts. In a handmade drawing, whether on an electronic tablet or on paper, in that location are intonations, traces of intentions and speculation. This is non different the way a musician might intone a note or how a riff in jazz would be understood subliminally and put a smile on your face.

This is quite different from today's "parametric design," which allows the computer to generate form from a set of instructions, sometimes resulting in so-chosen hulk compages. The designs are circuitous and interesting in their own way, but they lack the emotional content of a design derived from hand.

Working with today'due south computer-savvy students and staff it is evident that something is lost when they draw but on the figurer. It is coordinating to hearing the words of a novel read aloud, when reading them on paper allows us to daydream a little, to make associations across the literal sentences on the folio.

Similarly, drawing past hand stimulates the imagination and allows united states of america to speculate about ideas, a practiced sign that we're truly alive.

Source: https://core-services.org/architecture-and-the-lost-art-of-drawing-an-excerpt-from-michael-graves/

0 Response to "Michael Graves Architecture and the Lost Art of Drawing"

Post a Comment